Pollinators

You might not immediately see the connection between birds and bugs and clean water, but it’s a connection that is growing every year—literally! While the native plants capture, clean, and store rain water in their leaves, stems, trunks, branches, and roots, they are also busy providing food and habitat for pollinators. Less runoff polluting our water, more beneficial pollinators doing their important work. Maybe the next time you take a drink of water you should thank a bee or a hoverfly or a beetle or a hummingbird for a job well done!

Why is Pollination Important?

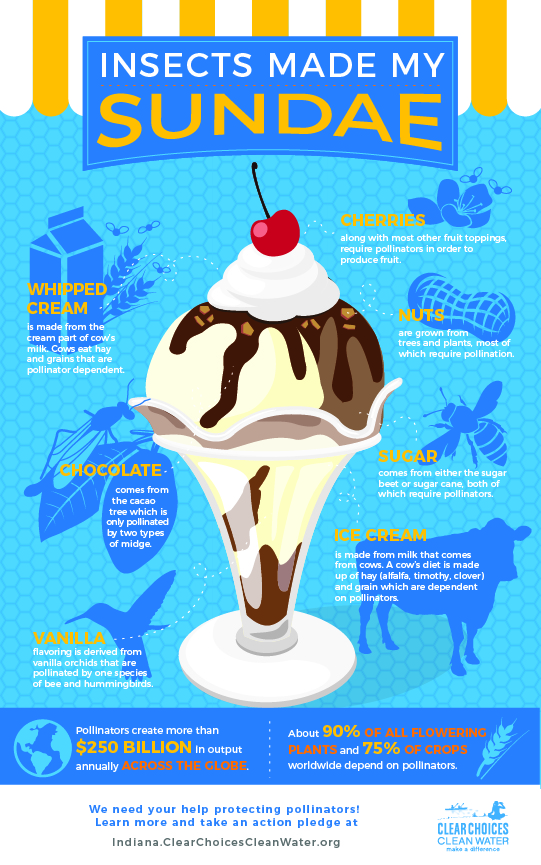

Pollinators are critical to today’s agricultural success, affecting about 320,000 different crops. In fact, more than a third of crops worldwide rely on pollination as well as products like beeswax candles and lip balm. They are also responsible for the reproduction of most of the plants in the natural world.

Who are the Pollinators?

A pollinator is any insect or animal that moves pollen from the reproductive parts of one plant to the reproductive parts of another plant. Pollen is collected on a pollinator’s body while it is feeding on a flower or plant and transferred to a new plant as the pollinator goes about its business. The flower then uses the pollen to produce a fruit or seed.

As you will see, many insects, birds, and mammals act as pollinators. And while honey bees might be the best-known pollinator, it is actually our native bees that are the most efficient and prolific at the job.

Bees

Bees are probably the most well-known and best of all the pollinators. Honey bees, bumble bees, carpenter bees, sweat bees…the list goes on. The best pollinators by far are bees native to a region, and there are over 4,000 species of them! This includes mason bees, leaf cutter bees, digger bees, bumble bees, and more. How efficient are these native bees? Just 300 orchard mason bees, Osmia lignaria, can do the same job as 90,000 honey bees! Honey bees are not native to the United States, but they are widely used in agricultural production.

Yellow jackets, hornets, and wasps–the insects most often confused with bees–also do a little pollinating work. However, they aren’t very efficient at it, because they aren’t fuzzy like bees.

Butterflies and Moths

Butterflies are another well-known pollinator, though they aren’t all that efficient at it because of their body structure. When a butterfly lands on a flower, it has very little contact with the pollen because of its long, thin legs. Butterflies also typically land on the side of flowers and use their long proboscis (tongues) to probe for nectar instead of crawling down into the flower like some other insects do. Moths are relatives of butterflies and also participate in pollination. Because moths are nocturnal, they tend to do their work at night, visiting mostly white, fragrant flowers.

Birds

Birds are key to the pollination of many wildflower species throughout the world, as well as a few food crops, like bananas, in tropical regions. Over 2000 species of bird are associated with pollination activities. In the United States, the hummingbird is vital to wildflower pollination, and a healthy wildflower population is crucial to a healthy ecosystem.

Bats

While the large majority of bats in the United States eat insects, some species from desert and tropical climates are pollinators. Bats are the major or exclusive pollinator for over 500 plant species, including those that give us tequila, mangoes, and guavas.

Hover Flies and Others

Many other insects and animals are top-notch pollinators, too. For instance, the hover fly (also known as a flower fly) is one of the most efficient pollinators out there. Hover flies are hard workers in orchards, pollinating fruit crops such as apples, cherries, peaches, pears, plums, and raspberries to name a few. They look like sweat bees with their black and yellow stripes, but they are flies and do not possess a stinger. You can tell the difference by the way they hover in place—bees can’t do that!

And don’t forget about beetles! Beetles were among the first pollinators and continue to pollinate plants today. When a beetle visits a flower it usually isn’t there to sip on nectar, but instead chews and eats parts of the plants it pollinates. Finally, you might also see spiders, ants, mosquitos, and even lizards carrying pollen.

Threats to Pollinators

There are a variety of causes of the decline in pollinator populations. By and large, these causes are the consequences of human activity, and today we have a clear idea of what we need to do in order to reverse our impacts.

Pests and Disease

The Varroa mite is a parasitic arthropod that infests honey bee colonies and is the main cause of colony collapse. Varroa mites also play a role in most of the 20 viruses known to infect honey bees, and these diseases have ravaged bee populations in recent years.

Pesticides and Other Household Chemicals

Pesticides include herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, and others. If you must use them, look for the Bee Advisory label when selecting a pesticide, and use this guide to avoid the most harmful types. If you are a commercial pesticide applicator, be sure to review this information from Purdue Extension.

Many of the household treatments we commonly use—things like mosquito deterrents and basic garden chemicals—have been found to have a negative impact on pollinators. Consider reducing or eliminating your use of these chemicals.

If you have concerns about pesticides and their effects on pollinators, contact the Office of the Indiana State Chemist (OISC).

Habitat Loss

Imagine needing food, but the only grocery store is in another town. Or you’re trying to build a house when there’s no lumber around. As we build more neighborhoods, shopping centers, parking lots, and offices, we are replacing pollinator habitat—all the things required for survival—with sterile grass, asphalt, concrete, and other human-made structures. If we want to keep what we have, then we need to put the habitat back into our landscapes.

Forage and Habitat

Help pollinators thrive using native plants, meeting other habitat needs, and changing how you manage your yard.

Plants

Click here for a list of the best native plants for pollinators from Purdue. If you would like to see a sample planting plan using some of our favorite native plants, click here.

There are also many trees and shrubs that support pollinators. Check out this guide for more options and be sure to take a look at this resource from Purdue Extension.

Yard Maintenance

If using native plants isn’t in your immediate future, consider leaving a portion of your property unmown or restrict mowing to early morning or evening when pollinators are least active. This allows bees to use some of the forage that may naturally occur in your yard or fields, plants like clover and dandelions. If you’re willing to stop treating your lawn with typical ‘weed and feed’ products, you will help make an even bigger difference, since lawn treatments include chemicals that have an impact on pollinators.

Ground Cover

Using valuable native plants isn’t the only way to support pollinators. Roughly 70% of native bees nest in the ground. Some build burrows into well-drained, bare, or partially vegetated soil. Other nest in abandoned beetle houses or in soft-centered, hollow twigs and plant stems. Bees will also colonize in dead trees and branches. If you have an underutilized area on your property, use this guide to create the kind of environment to support bees!

Water

Access to water is a key element of quality habitat. Consider keeping a small dish of water available near your nectar sources. Be sure to dump out the contents and refill fresh water on a daily basis in order to prevent diseases from spreading and mosquitos from breeding.

Who Do I Contact with Questions about Pesticides?

If you have concerns about pesticides and their effects on pollinators, the Office of the Indiana State Chemist (OISC) is who you need to contact. It is their job to administer laws associated with pesticides and help protect the environment. You can call them toll free at (800) 893-6637.

The state pollinator protection plan is available for your review. Access the document here: Indiana Pollinator Protection Plan